Today author Alan M. Clark takes over our blog to tell us about "Nipper Dippers, Mug-hunters, and Bludgers: Dangers on the Streets of the Victorian East End", around the time of Jack The Ripper.

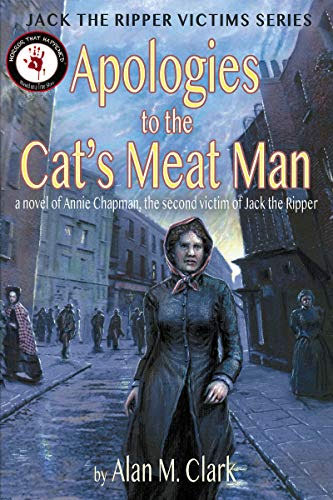

Today author Alan M. Clark takes over our blog to tell us about "Nipper Dippers, Mug-hunters, and Bludgers: Dangers on the Streets of the Victorian East End", around the time of Jack The Ripper.Alan M. Clark is the author and illustrator of the Jack the Ripper Victims Series, a Crime Horror series (IFD Publishing).

"…I regard the five books that make up this series as unarguably one of the high points in Ripper fiction over the past 130 years." —David Green, Ripperologist magazine

"Alan M. Clark has given us a great gift with his Jack the Ripper Victims series. I no longer care who the murderer was, for I know who his victims were. Exhaustively researched and true to period, Clark artfully relates their stories with clarity and compassion…" —Stephen T. Vessels, Thriller Award nominated author of The Mountain and the Vortex and The Door of Tireless Pursuit.

|| The Series || Trailer || The Books || Teaser: Exclusive Excerpt || Teaser: Alan's JTRV Quiz || Author Guest Post || About the Author || Giveaway & Tour Stops ||

"Nipper Dippers, Mug-hunters, and Bludgers: Dangers on the Streets of the Victorian East End

Writing the Jack the Ripper victims Series, I used in the dialogue a lot of old slang—also called street cant or thieves cant. Much of the slang speaks to the criminal element of the time. The research into the various forms of cant also gave me a larger awareness of just how rife with crime were the streets of London in the late Victorian era. While this post is meant to celebrate the re-release of all five novels in the Jack the Ripper victims Series with new covers, some with new illustrations, it’s also my effort to give a sense of the character of the time and to show some similarities with our time.

To understand the extraordinary furor in London over the Ripper killings, one must know something about the frequency and variety of death that already occurred within the East End of the time. For those with something of value to lose, dangers aplenty existed on the streets in the form of criminals with clever or violent ways to take from others. A life might end suddenly at the point of a knife or with the sound of a “barker “ (pistol), but the murder rate was actually quite low. Weapons were more often used in robbery as a threat to life. If the “mark” or “pigeon” complied, he or she got away with little or no physical harm.

I was robbed on the street in San Francisco in the 1970s, and got away slightly poorer, but unharmed. The weapon used as threat in that case was a big dog.

The dangers for the poor on London’s Victorian era East End streets had to do mainly with bad water, disease, debt, and possible drunken misadventure, either through violence or accidents. Disease took most lives at a younger age than today, primarily illnesses from exposure to bacteria and viruses. The idea of such germs was not universally accepted in that period, and what understanding there was of how they interacted with human beings was woefully incomplete. London’s East End was a wretched, filthy place, parts of which housed 800 people per acre.

The rate of industry-related deaths (violent accidents or chemically induced on the job) was quite high, as was the suicide rate and the infant mortality rate—reported as at least 30% (probably closer to 50%) died before the age of five. The average human being had an expected life span of around forty years.

Many prostitutes were brutalized and much violent crime occurred during the years between 1887 to 1889, yet few of the killings were seen to be murders. Perhaps this is attributable to the desire of authorities to keep quiet about the crime rate during a time of swift economic change and social upheaval. Whatever the case, the violence characteristic of the Ripper killings, with multiple stabbings and apparent degradation of the victims suggesting piquerism (a sexual desire to puncture flesh with a sharp object) on the part of the killer, certainly surprised the citizens of London.

|

| Eliza Fallon made her living turning tricks (Ancestry.co.uk and Tyne & Wear Archives) |

|

| In 1870 Edgar Kilminster, seven, was sentenced to seven days hard labour and 12 strokes with the birch for stealing sweetmeats (Gloucestershire Archives) |

The title of this post employs Victorian-era British slang expressions. “Nippers” are small children, most often boys. Frequently they were street children, not uncommonly engaged in criminal behavior like picking pockets (a “dipper”) and other thievery. “Mug hunters” are muggers, most often desperate men willing to rob by roughing someone up. A “bludger” is a violent criminal. The image below is one of a man arrested for mugging.

|

| In 1870 James Logan, 20, stole a coat; he was sentenced to one month of hard labour in Oxford Castle Prison |

Here are terms for pickpockets and their activities:

A pickpocket was a “fag,” “dipper,” “tooler,” or, if highly skilled, a “FineWirer.”

Picking pockets was to “hook” or it could be referred to as “buzzing” or, if done skillfully, “tooling.”

Lightly feeling someone’s clothing in passing to locate valuables was to “fan.”

“Cly faking” was to steal handkerchiefs, preferably silk ones.

“Flimp” means to snatch and run, usually done in a crowded place. Children were particularly good at this.

“Hoisting” or “palming” was shoplifting.

A “kids man” was one who organized child pickpockets and thieves (Fagin, in Dicken’s Oliver Twist was one)

A “maltooler” picked pockets while riding the omnibus.

A “toygetter” was one who stole pocket watches.

A pickpocket was a “fag,” “dipper,” “tooler,” or, if highly skilled, a “FineWirer.”

Picking pockets was to “hook” or it could be referred to as “buzzing” or, if done skillfully, “tooling.”

Lightly feeling someone’s clothing in passing to locate valuables was to “fan.”

“Cly faking” was to steal handkerchiefs, preferably silk ones.

“Flimp” means to snatch and run, usually done in a crowded place. Children were particularly good at this.

“Hoisting” or “palming” was shoplifting.

A “kids man” was one who organized child pickpockets and thieves (Fagin, in Dicken’s Oliver Twist was one)

A “maltooler” picked pockets while riding the omnibus.

A “toygetter” was one who stole pocket watches.

The woman in the image below was arrested for stealing a watch.

|

|

Isabella Dodds was jailed for stealing a gold watch (Ancestry.co.uk and Tyne & Wear Archives) |

Here are some Victorian era slang terms for criminals and their activities:

A person who engaged in crime and violence was a “rampsman.”

To “go out” was to turn to thievery.

A “prig” was a thief.

“Click” was a robbery or theft.

To steal was to “min,” “mizzle,” “nick,” “nail,” or “knap.”

To be doing something admirable to criminals was said to be “doing something class.”

“Caper” was a criminal act, dodge, or device.

“The Family” was members of the criminal world as a group.

“Flash house” was a pub frequented by criminals.

A small-time criminal was a “gonoph.”

To be knowledgeable about criminals or criminal methods was “to know life.”

A criminal of all work was called a “lurker.”

A slightly built criminal who broke in through tight spaces to rob was a “snakesman.”

A thief who distracted by throwing snuff to cause his victim to sneeze was called a “sneeze-lurker.”

A thief who stole from drunks was a “mutcher.”

A “roller” was one who robbed drunks or was a prostitute who stole from clients.

A “snoozer” robbed those who were sleeping, often breaking into a house or an inn and getting away without awakening the victims.

The “highwayman” robbed along roads; the“footpad” robbed people walking the road, and the“dragsman” stopped coaches along the road to rob those riding within.

One who gained payment through protection racket or a threat of violence was called a “demander.”

A “cracksman” was one who broke into locked areas, safes, and strongboxes. Breaking and entering for theft was “cracking a crib.”

To “christen” or “church” a stolen watch was to remove any identifying marks before trying to sell or pawn it.

A “dub’ or “betty” was a lock pick.

A “jemmy” or “rook” was for breaking into a house.

A “duffer” sells things that are stolen.

“Ikey” or “fence” was one who receives stolen goods.

Burgling through a window was a “jump.”

To steal from children was “kinchen lay.”

A “screever” was a forger.

A person who engaged in crime and violence was a “rampsman.”

To “go out” was to turn to thievery.

A “prig” was a thief.

“Click” was a robbery or theft.

To steal was to “min,” “mizzle,” “nick,” “nail,” or “knap.”

To be doing something admirable to criminals was said to be “doing something class.”

“Caper” was a criminal act, dodge, or device.

“The Family” was members of the criminal world as a group.

“Flash house” was a pub frequented by criminals.

A small-time criminal was a “gonoph.”

|

| In January 1873 Thomas Thompson, 14, stole one shilling; he was sentenced to 21 days hard labour at Wandsworth Prison |

To be knowledgeable about criminals or criminal methods was “to know life.”

A criminal of all work was called a “lurker.”

A slightly built criminal who broke in through tight spaces to rob was a “snakesman.”

A thief who distracted by throwing snuff to cause his victim to sneeze was called a “sneeze-lurker.”

A thief who stole from drunks was a “mutcher.”

A “roller” was one who robbed drunks or was a prostitute who stole from clients.

A “snoozer” robbed those who were sleeping, often breaking into a house or an inn and getting away without awakening the victims.

The “highwayman” robbed along roads; the“footpad” robbed people walking the road, and the“dragsman” stopped coaches along the road to rob those riding within.

One who gained payment through protection racket or a threat of violence was called a “demander.”

A “cracksman” was one who broke into locked areas, safes, and strongboxes. Breaking and entering for theft was “cracking a crib.”

To “christen” or “church” a stolen watch was to remove any identifying marks before trying to sell or pawn it.

|

| At the age of 27, William Dazley, an ironmonger's assistant, was sent to Bedford Prison for stealing (Bedfordshire Archives & RecordsService) |

A “dub’ or “betty” was a lock pick.

A “jemmy” or “rook” was for breaking into a house.

A “duffer” sells things that are stolen.

“Ikey” or “fence” was one who receives stolen goods.

Burgling through a window was a “jump.”

To steal from children was “kinchen lay.”

A “screever” was a forger.

Currently in a Tech-Revolution, we see a situation with some similarities to the Industrial Revolution, one in which the numbers of employment opportunities are diminishing. Employers phaseout hiring positions as work is increasingly given to automated systems and artificial intelligence.

|

| In 1870, Robert Woodley, 18, spent 21 days hard labour in Oxford Castle Prison for stealing hay. |

Here are types of beggars from Victorian London:

A beggar was a “mumper,” “bareman,”or a “gegor”

“Griddling” was the act of begging.

A “fakement” was a pretense for begging.

“On the blob” was a term for someone who begged while telling a hard-luck story.

The “Scaldrum dodge” was to beg while pretending to be handicapped, often faked with self-inflicted wounds.

“Working the shallow” was begging while half naked, and a “shivering Jimmy” was a half naked beggar in rags.

A “bunter” was a beggar/prostitute.

A “glim” was one who begged while pretending to have lost a home to fire, sometime exhibiting faked burns.

The “shake lurk” was the act of begging while pretending to be a seaman having suffered in a shipwreck.

A beggar was a “mumper,” “bareman,”or a “gegor”

“Griddling” was the act of begging.

A “fakement” was a pretense for begging.

“On the blob” was a term for someone who begged while telling a hard-luck story.

The “Scaldrum dodge” was to beg while pretending to be handicapped, often faked with self-inflicted wounds.

“Working the shallow” was begging while half naked, and a “shivering Jimmy” was a half naked beggar in rags.

A “bunter” was a beggar/prostitute.

A “glim” was one who begged while pretending to have lost a home to fire, sometime exhibiting faked burns.

The “shake lurk” was the act of begging while pretending to be a seaman having suffered in a shipwreck.

|

| In January 1873 Thomas Casey, 13, stole a rabbit and he was sent to Wandsworth Prison where he was whipped and given four days hard labour |

Here are slang terms concerning cons and grifters:

To “mace” was to cheat, and a “macer” was a cheat.

To be on the “mag” was to be involved in a cheating scheme, and a “magsman” or “mobsman” was a swindler, often one who looked like he was well-to-do.

A “bearer up” used a woman as decoy to distract a man, then robbed him.

“Snide” was counterfiet coin.

A “bit faker” or “coiner” was a counterfeiter.

“Shoful” was counterfeit money.

A “shofulman” or “smasher” was one who passed counterfeit money.

“Black” referred to blackmail.

A “bonnet” was a covert confederate for a swindler

To cheat at cards was “broading,” while the one doing so was called a “broadsman.”

A “buck cabbie” was a dishonest cab driver.

“bug hunting” was robbing or cheating drunks.

A “buttoner” lured victims to a swindler.

To “play the crooked cross” was to swindle, betray or cheat.

A “fakement” was a con, a device, or a pretense.

A “gray” or “grey” was a coin with the same face on either side.

A “sharp” was a card shark.

To “mace” was to cheat, and a “macer” was a cheat.

To be on the “mag” was to be involved in a cheating scheme, and a “magsman” or “mobsman” was a swindler, often one who looked like he was well-to-do.

A “bearer up” used a woman as decoy to distract a man, then robbed him.

“Snide” was counterfiet coin.

A “bit faker” or “coiner” was a counterfeiter.

“Shoful” was counterfeit money.

A “shofulman” or “smasher” was one who passed counterfeit money.

“Black” referred to blackmail.

A “bonnet” was a covert confederate for a swindler

To cheat at cards was “broading,” while the one doing so was called a “broadsman.”

A “buck cabbie” was a dishonest cab driver.

“bug hunting” was robbing or cheating drunks.

A “buttoner” lured victims to a swindler.

To “play the crooked cross” was to swindle, betray or cheat.

A “fakement” was a con, a device, or a pretense.

A “gray” or “grey” was a coin with the same face on either side.

A “sharp” was a card shark.

|

|

Henry Leonard Stephenson, 12, was a real-life Oliver Twist character; he was sent to Newcastle City Gaol for two months after being convicted for breaking into houses (Tyne & Wear Archives) |

Here are some terms for policemen:

“Peelers,” “beagles,” “blue bottles,” “pigs,” “rozzers,” “mutton shunters,” “Bobbys,” “crushers,” “Miltonians,” and “slops.”

“Peelers,” “beagles,” “blue bottles,” “pigs,” “rozzers,” “mutton shunters,” “Bobbys,” “crushers,” “Miltonians,” and “slops.”

Laws in Victorian England protected the rights to property—to possess articles, commodities, land, wealth, even women—more vigorously than they did human rights.

In the United States today, rather than asking the well-to-do to give more of their wealth to the effort of creating more opportunity for all, society finds it easier to lock away those who turn to criminal activities in order to survive.

Here are slang terms for prison or jail (British spelling gaol):

Prison was “stir.”

Jail (British spelling gaol) was “crib,” “drum,” or “bucket and pail.”

To be in imprisoned was to be “lagged,” “away,” “quod,”or doing “bird.”

A “stretch” was typically a one year sentence.

A “drag” was typically a 3 month jail (British spelling gaol) sentence.

To “get transportation” or to “get the boat” meant that you were convicted and would spend your sentence in the penal colony in Australia.

A “turnkey” was a prison warden or jail keeper.

Prison was “stir.”

Jail (British spelling gaol) was “crib,” “drum,” or “bucket and pail.”

|

| In 1870, James Freeman was locked up in Oxford Castle Prison for 21 days for stealing a loaf of bread |

A “stretch” was typically a one year sentence.

A “drag” was typically a 3 month jail (British spelling gaol) sentence.

To “get transportation” or to “get the boat” meant that you were convicted and would spend your sentence in the penal colony in Australia.

A “turnkey” was a prison warden or jail keeper.

One of the points to all this slang in Victorian times, was to render what was said unintelligible to non-criminals. Another point to slang, what ever the era, is to create a separate society within the the greater society, one connected by a common speech pattern.

Smart? If you’re shut out of the greater, I suppose it pays to know who your people are.

The Jack the Ripper victims Series is meant to give readers a taste of what it was like to walk in the shoes of the women the Whitechapel Murderer killed, to provide a sense of their time and circumstances, and bring some understanding of the struggles of that society, and particularly of women in the Victorian period.

—Alan M. Clark

Eugene, Oregon

Horror that happened...

No comments:

Post a Comment